Tradition tells us that when tromping off into the thick of a good science fiction story a reader suspends her disbelief , that when she picks up a story to read it, she says to herself, “Hey, I know that there’s no such thing as intergalactic spaceships, time travel, and ruptures in the space-time continuum, but for the sake of having a little fun, hearing a good story, I guess I’ll go along with it.” But for a moment, let's consider this from another angle. Let's say that perhaps the best science fiction does not ask us simply to suspend our disbelief, rather it asks us to ascend our belief. It asks to say to ourselves that perhaps what we have never before accepted in our heart of hearts could indeed be possible. And when we look at it from this angle, we find that there is such a rich history of realized examples to pull from. People dreamed of outer space long before they sent up their dogs and monkeys to test out the waters. William Gibson, author of Neuromancer (1984) coined the term “cyberspace” and envisioned the Internet before it existed...

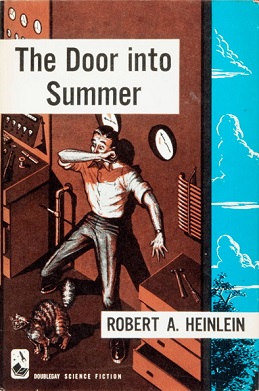

So, in honor of the potential of science fiction, and in fact, the potential of what we can discover in the world around us, and in ourselves. I’m breaking earth on this blog with an excerpt from Robert Heinlein’s “Doorway into Summer." First published in 1957, Heinlein invents, in fiction, a simple device: the automated floor vacuum. You may know it now as the Roomba. I’m following it, below, with Heinlein's casual description and vision of Autocad, the crucial design software now used by architects and engineers the world over.

"What Hired Girl would do (the first model, not the semi-intelligent robot I developed it into) was to clean floors ... any floor, all day long and without supervision. And there never was a floor that didn't need cleaning.

It swept, or mopped, or vacuum-cleaned, or polished, consulting tapes in its idiot memory to decide which. Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray on its upper surface, for someone brighter to decide whether to keep or throw away. It went quietly looking for dirt all day long, in search curves that could miss nothing, passing over clean floors in its endless search for dirty floors. It would get out of a room with people in it, like a well-trained maid, unless its mistress caught up with it and flipped a switch to tell the poor thing it was welcome. Around dinner time it would go to its stall and soak up a quick charge -- this was before we installed the everlasting power pack."

(Heinlein, 20-21)

It swept, or mopped, or vacuum-cleaned, or polished, consulting tapes in its idiot memory to decide which. Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray on its upper surface, for someone brighter to decide whether to keep or throw away. It went quietly looking for dirt all day long, in search curves that could miss nothing, passing over clean floors in its endless search for dirty floors. It would get out of a room with people in it, like a well-trained maid, unless its mistress caught up with it and flipped a switch to tell the poor thing it was welcome. Around dinner time it would go to its stall and soak up a quick charge -- this was before we installed the everlasting power pack."

(Heinlein, 20-21)

and ...

"By the time I got to Miles's house I was whistling. I had quit worrying about that precious pair and had worked out in my head, in the last fifteen miles, two brand-new gadgets. One was a drafting machine, to be operated like an electric typewriter. I guessed that there must be easily fifty thousand engineers in the U.S. alone bending over drafting boards every day and hating it, because it gets you in your kidneys and ruins your eyes. Not that they didn't want to design -- they did want to -- but physically it was much too hard work.

This gismo would let them sit down in a big easy chair and tap keys and have the picture unfold on an easel above the keyboard. Depress three keys simultaneously and have a horizontal line appear just where you want it; depress another key and you fillet it in with a vertical line; depress two keys and then two more in succession and draw a line at an exact slant.

Cripes, for a small additional cost as an accessory, I could add a second easel, let an architect design in isometric (the only way to design), and have the second picture come out in perfect perspective rendering without his even looking at it. Why, I could even set the thing to pull floor plans and elevations right out of the isometric."

(Heinlein, 40)

"By the time I got to Miles's house I was whistling. I had quit worrying about that precious pair and had worked out in my head, in the last fifteen miles, two brand-new gadgets. One was a drafting machine, to be operated like an electric typewriter. I guessed that there must be easily fifty thousand engineers in the U.S. alone bending over drafting boards every day and hating it, because it gets you in your kidneys and ruins your eyes. Not that they didn't want to design -- they did want to -- but physically it was much too hard work.

This gismo would let them sit down in a big easy chair and tap keys and have the picture unfold on an easel above the keyboard. Depress three keys simultaneously and have a horizontal line appear just where you want it; depress another key and you fillet it in with a vertical line; depress two keys and then two more in succession and draw a line at an exact slant.

Cripes, for a small additional cost as an accessory, I could add a second easel, let an architect design in isometric (the only way to design), and have the second picture come out in perfect perspective rendering without his even looking at it. Why, I could even set the thing to pull floor plans and elevations right out of the isometric."

(Heinlein, 40)

No comments:

Post a Comment